Monday, 28 September 2009

Monday, 21 September 2009

Bring a problem parties - speed therapy

To begin with, three observations. First, a pint is about the right length to talk over many problems. A pint shared lasts half an hour. With a good interlocutor, there is not much that you can't get some helpful insight on in half an hour. Second, independent advice on problems - be they emotional, practical or technical - is often useful. OK, I wouldn't ask the check out person in my local supermarket for advice on solving a high dimensional PDE, but often a random stranger can be helpful. Third, speed dating proves that if an experience is potentially interesting and short enough that a bad encounter is soon forgotten, then (some) people will sign up.

So, bring a problem parties. A selection of people, each with a problem. They are randomly matched into pairs, with one person selected as the solver, the other as the questioner. The questioner buys the drinks and presents his or her problem. The solver tries to help. After half an hour, a bell rings, and another round begins, with solvers as questioners and vice versa. Four rounds would be two hours, and you would be guaranteed two perspectives on your problem. It would also make for a more interesting evening than most. If you franchise it, cut me in please.

Labels: Fun

Saturday, 19 September 2009

A manifesto

The rules I set were to write down no more than two sentences in ten different areas. In no particular order:

- Education. Abolish the charitable status of private schools, and fold academies back into the ordinary state school system. Abolish student grants and increase university funding, including research funding, very substantially.

- Transport. Abolish road tax, increase petrol duties significantly, and eliminate the special treatment of airlines, including VAT on airline fuel. Invest substantially in carbon efficient transportation infrastructure including trains, buses and cycle networks.

- Taxation. Simplify the personal and corporate tax system, impose draconian penalties on any form of avoidance, and remove the non-dom status completely. Eliminate UK-linked tax havens such as Cayman, Jersey and Bermuda by forcing them either to join the UK tax code or removing their protection.

- Energy. It is too late for fission, so invest heavily in renewables and in energy saving. Push hard for fusion because if we can crack that one, energy becomes a non-issue.

- Defence. Cancel the expensive toys like the Trident replacement. Provide the ordinary soldier with the resources they need, like body armour and IED-proof vehicles.

- Foreign Affairs. Engage more positively with the EU. Revive Robin Cook's ethical foreign policy.

- Constitutional Reform. Introduce proportional representation and a fully elected House of Lords. Disestablish the Church of England and secularise the state, recognising the rights of believers and non-believers equally.

- Finance. Break up the majority state owned megabanks, Lloyds and RBS. Make capital requirement proportional to size to encourage a diverse system of banks that are not too big to fail.

- Liberty. Cancel the id cards project and other big database projects. Enact legislation to protect our historic liberties and roll back both state and private surveillance and data gathering.

- Industrial Policy. Develop a comprehensive policy across education, development aid and innovation support to encourage manufacturing and export-based industries, especially outside the South East. Reduce financial and other services as a percentage of the total economy.

Labels: Politics

Thursday, 17 September 2009

Keynesian traps and flooding the building

A very rough and brutal sketch of Keynes' classical account of the savings trap is that if people save too much, rather than consume, then the velocity of money drops, inventory builds up, growth falls (and even goes negative) as businesses cut back on production. A standard account of the liquidity trap by Krugman is here.

How does the Phillip's device help? Well, it points out a truth that is often hard to see, namely that money can only be created or destroyed by the central bank. Credit cannot be 'created' without funding; money cannot disappear. These days, rather little money is stored in mattresses or bank vaults: most of it is in the form of bank deposits, securities, or other investments. And of course those assets are someone else's liabilities, i.e. funding for them. Thus these days your choice is not between putting your cash under the bed and spending it: it is between putting it in a bank - which will lend it to someone else - and spending it. In this sense saving is not quite as bad as in the classical Keynesian account, as it provides funding for corporations and individuals who do want to engage in economic activity. Even buying government bonds is not useless as the government spends the money on something.

Now of course the increase in economic activity provided by a dollar of spending on goods may be rather more than that provided by a dollar of bank deposits. But it is worth noting that the dollar of bank deposits are not useless: the bank has to do something with your money, and that something probably has positive economic value. Anything else would cause funds to build up rather too fast at the bank - something the Phillip's computer would model as water flooding out...

Labels: Economic Theory, Liquidity risk

Thursday, 10 September 2009

One of the many reasons I am depressed

I believe the brain trust behind the Obama White House has made a huge tactical error.I agree with the conclusion: and it is deeply depressing for those of us who have devoted a lot of energy to arguing for reform.

As Rahm Emmanuel likes to say, one should “never waste a crisis” — and the White House has done just that...

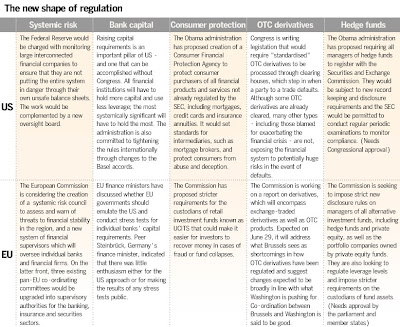

There was widespread popular support for a full reform of finance. What the White House should have pursued was: 1) Reinstatement of Glass Steagall; 2) Repeal the Commodity Futures Modernization Act; 3) Overturning SEC Bear Stearn exemption allowing 5 biggest firms to leverage up far beyond 12 to one; 4) Regulating the non bank sub-prime lenders; 5) Continuing high risk trades to be compensated regardless of profitibility; 6) Mandating (and enforcing) lending standards, etc...

Instead, we have a White House that appears adrift, and the most importantly, may very well have missed the best chance to clean up Wall Street in five generations.

Ritholtz's prescription isn't quite mine: I am less convinced about the benefits of a Glass-Steagall style split, not least because many European banks managed to be universal without being dangerous; rather I would prefer to see action to split up too big to fail institutions, combined with increased regulatory capital requirements that really constrain leverage for all systemically important risk takers. But the details don't really matter: doing something does.

Labels: Regulation

Monday, 7 September 2009

Adair dares, and other unlikely tales, updated

(Update: I should really say something about why Tobin taxes are good from a financial stability perspective. The point is that they introduce more friction into the financial system. Even a small absolute increase in bid/offer spread, when spreads are low, dramatically reduces arbitrage opportunities, and thus 'useless' financial activity. A real money transaction - driven by global trade for instance - would not notice an extra 0.05% on their FX rate; but a program trading volatility would. The same applies in the equity markets: one way to reduce the impact of high frequency trading is simply to make it (marginally) more expensive.

It is interesting to see Lloyd Blankfein, Goldman Sachs' CEO, agreeing with Turner that some of finance had become socially useless. There were always useless parts, of course, but the fraction has grown significantly over the last 20 years.)

So how would we make this work? Well, how about this for a Europe-wide proposal. Transactions physically done in Europe are taxed. In order to (a) sell securities to a European domiciled investor, (b) take deposits in Europe or (c) trade derivatives, FX or repo with a European counterparty, you have to demonstrate that you pay the tax on your global business too (although not necessarily to a European government: any old government will do). OK, some banks would decide to leave Europe entirely. But most wouldn't if the level of the tax was sufficiently low...

Thursday, 3 September 2009

HRbots and the false comfort of quantification

Catbert immediately to mind when I read a Netflix presentation on their corporate values (hat tip Felix Salmon - who seems to have subsequently deleted the longer laudatory post about these slides). To precis hugely, Netflix say that they want the best people, they reward them at the top of the market so that they don't want to leave, and they get rid of the merely mediocre.

A moment's inspection of course reveals this to be an utter crock, in best Catbert tradition. First, it assumes that the firm's internal mechanisms can tell if a person is any good or not. Second it assumes that being good is invariant over time: if you are good today, you'll be good tomorrow; and if not, not. And third it assumes that a company full of good people is somehow a good thing. All of these are false.

Appraisal mechanisms, 360 feedback (or 720 or whatever) and the like are fascinating and important (from a financial standpoint) games. But I have never come across ones that do not simply validate manager's prejudices. They often bear essentially no relationship to job performance.

The second point is even more important. An employee can be useful in some situations and less so in others. They can sit around for ten years doing nothing much useful, then save the firm. Or they can make a reasonable contribution every year without ever being a star. They can (and in the case of star executives often do) perform wonderfully for years then suddenly screw up massively.

The most pervasive HR lie of all, though, is that somehow it is in the company's interests to have 'the best' employees. Have you ever tried managing a team of star performers? It makes herding cats look easy. They get bored; they all want to know what their career progression is; they fight. I'd much rather have one or two good people and a leavening of average performers. More will get done.

Furthermore, firms need diversity. They need it for the simple business reason that conditions change. If you staff up to optimise for environment X, and then suddenly find you are operating in environment Y, then you are likely to fail. But if you have a bunch of reasonably OK people who are willing to put in a decent day's work for a decent day's pay, then they will probably change what they do to help you out. Their self worth is not tied up with being the best person in the world at their job, and so they will probably not get depressed and sulky when it turns out that they aren't any more.

No, meritocracy is a very dangerous concept. It assumes you can identify the meritorious, and that it is in the firm's interests to have more of them. The more I see of firms, the more convinced I am that neither of those two things is true. Hire some reasonable people. Pay them reasonably. But don't whatever you do ever make the mistake of believing anything someone from HR tells you.

Labels: Organisation Structure

Monday, 31 August 2009

Thursday, 13 August 2009

This collateral smells a bit off

The vaults of Credito Emiliano SpA hold the pungent gold prized by gourmands around the world -- 17,000 tons of parmesan cheese.I love commodities finance. Particularly when you can eat the collateral if the loan goes bad.

The regional bank accepts parmesan as collateral for loans... [its] two climate-controlled warehouses hold about 440,000 wheels worth 132M Euros...

The bank offers loans for as long as 24 months, equal to the time it takes the parmesan to age, at the euro interbank offered rate, plus 0.75-2%.

Labels: Credit

Wednesday, 12 August 2009

Excess Liquidity

in their anti-deflationary fervour, central banks may be creating more money than depressed economies require. The surplus creates "excess liquidity" - which may be feeding a new series of stock, commodity, property and bond bubbles...Excess liquidity is a really hard thing to estimate, as it is the difference between two really big numbers: the supply of money, and the economy's demand for money. But this really is a Goldilocks situation: you want the money supply to be just right for economic needs. If, perhaps because you are worried about the banking system's access to liquidity, you supply too much, then it is just going to be invested in financial assets, creating a bubble. Are we, I wonder, in the early phases of the first post Crunch bubble?

Sebastian Becker, an economist with Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt, defines excess liquidity as money supply that is surplus to the needs of real economic activity, and therefore free to be invested in financial assets. Becker combines monetary growth figures for the US, Japan, the eurozone, the UK and Canada and finds excess liquidity - measured as a rising stock of money to GDP - in these economies is now being created more rapidly than in the late 1990s stock-market bubble, or during the subsequent house price boom.

Labels: Liquidity risk

Tuesday, 11 August 2009

Monoline Death Watch

in a note issued this morning they said that MBIA’s tangible book value is actually negative, to the tune of about -$40 per share.OK, the full article has some caveats. But the mere fact that a reputable investment bank (if that is not an oxymoron) can suggest that MBIA is insolvent should raise some warning signs about the extended historical fiction that is insurance accounting.

Labels: Accounting, Insurance, Monoline

Monday, 10 August 2009

Reasons to stay flat?

Labels: Markets

Friday, 7 August 2009

Controlling complex systems

attempts at self-control result in a competition between independent processes and that the amount of top-down control biases the competition appropriatelyI am increasingly of the view that neuroscience has more useful things to say to finance than conventional economics does.

Labels: Rules

Inefficient Units of Currency

- Children

- Millstones

- Imaginary euros*

- Copies of Now That's What I Call Music! Vol. 7**

- Pieces of long-grain rice that are not actually very long

- Unicorn heads

- Canadian dollars

*Arguably, the ECU (which worked perfectly well as a currency) was imaginary.

**Vol. 7 is I suspect now a collector's item. The current volume is 73.

Labels: Fun

Thursday, 6 August 2009

The notable glibness with which the writer throws off chains of causation

Things here will be slow and less finance-oriented here for a little while for two reasons: firstly, I have been intending to move this blog away from blogger for some time, and I really want time to look into that. Secondly, the spectacle of the utter failure of reform is depressing me slightly, if not causing a Touretteish Torrent.

Wednesday, 5 August 2009

Creativity

... I’m left wondering what the word ‘creative’ means to people who can overcome difficulty by just being creative. It seems to be like an ingredient that’s available down the shops. If it’s necessary, you’ll get some and use it. Need to produce something? ‘Oh, just think creatively.’ I want to say, how do you think creatively? What is thinking creatively? But I don’t want to let on that I’m ignorant of a process everyone else seems to understand perfectly.I especially like `Creative writing? As opposed to?'

It’s a word I’ve never been able to use because I don’t know what it means really. Creative writing? As opposed to? Does it mean imaginative? OK, now imagination is called for. Right, there you go. How confident everyone seems to be about having the ability to be creative, and knowing what to do with it, and how very little effect it seems to have on the vast majority of products it is sprinkled on.

Labels: Fun

Tuesday, 4 August 2009

Deprogramming Obama

Labels: Economic Theory, Politics

Don't judge me

Paul Krugman has a post entitled Rewarding bad actors. He takes the view that two situations - the profits from high frequency trading at Goldman (and presumably elsewhere) and the payout to Andrew Hall at Citi's Philbro arm - are undesireable. The common thread, he says, is

Paul Krugman has a post entitled Rewarding bad actors. He takes the view that two situations - the profits from high frequency trading at Goldman (and presumably elsewhere) and the payout to Andrew Hall at Citi's Philbro arm - are undesireable. The common thread, he says, isin both cases we’re looking at huge payouts by firms that were major recipients of federal aid... What are taxpayers supposed to think when these welfare cases cut nine-figure paychecksNow, I happen to agree with Krugman that both of these situations suck. However, I think his characterisation of the problem is wrong. He says.

we’ve become a society in which the big bucks go to bad actors, a society that lavishly rewards those who make us poorerIn other words, the problem is bad people. That's too easy. It allows us to point out fingers and take no responsibility. No, the problem isn't evil people. The problem is that we have created a system where unhelpful actions are rewarded. It is the system that is at fault, not the actors. This means that many people are responsible: everyone who failed to promote or support change, and all of those who shaped and defended the current system. Yes, that does include me. But at least I am trying to promote a debate about what rules we need for the future.

Labels: Rules

Monday, 3 August 2009

Come backs

Labels: Sport

Saturday, 1 August 2009

Discrete, discreet trading

a discrete-time market mechanism (technically, a call market), where orders are received continuously but clear only at periodic intervals. The interval could be quite short--say, one second--or aggregate over longer times--five or ten seconds, or a minute. Orders accumulate over the interval, with no information about the order book available to any trading party. At the end of the period, the market clears at a uniform price, traders are notified, and the clearing price becomes public knowledge. Unmatched orders may expire or be retained at the discretion of the submitting traders.This is really a nice idea. Real users would notice no difference between a market discretised in ten second blocks and a continuous one, but at a stroke bad high frequency trading would be eliminated. Add in a minimum (but low) bid/offer spread too, and the system becomes significantly more robust. The high frequency traders can no longer take your money off the table.

Labels: Markets

Friday, 31 July 2009

Fact as fiction, and other storytelling techiques

360-Degree review systems, 24-hour response voice mail, and rotation of bankers through different departments only work when senior managers refuse to make exceptions to the rules. There are a nauseating number of investment banks which profess an undying commitment to teamwork and a dedicated focus on cultivating client relationships rather than chasing transactions. But these banks fall short time and time again because they do not enforce these principles. If Mr. Big Swinging Dick Managing Director who brings in a billion dollar IPO or a ten billion dollar merger throws a hissy fit and threatens to stomp out the door if he has to share credit, or a successful M&A banker refuses to manage a group in Capital Markets, or a Group Head inflates the review scores of all his subordinates to boost their pay and his power, senior management can either hold firm and preserve the culture, or they can cave. If they hold firm, everyone else at the bank hears about it, and they learn that the rules and the culture will be enforced. If they cave, everyone knows that too, and it's off to the bad old races of "what's in it for me." Sadly, most investment bank executive teams cave.Michael Lewis would have illustrated this story with a mildly amusing tale of bankerly bad behaviour. Other journalists would perhaps have tried to garner outrage before they had even finished making the point. But, being an insider, ED is smart enough to know that the sex, drugs and science fiction work best as garnishes for the real erudition.

Labels: Organisational Culture

Thursday, 30 July 2009

Sovereign credit quality and foreign currency borrowing

So, when can countries devalue their way out of trouble?

One important factor is the currency of debt. If most of a countries' debt is in local currency, then devaluation is more likely to be effective. Clearly you can use a combination of inflation and devaluation to reduce the real value of your debts. If you have a significant amount of debt - government or otherwise - in foreign currency, then things are a lot more difficult. This is partly why I am sceptical about buying the Icelandic recovery hook, line and sinker. (They are, after all, reliant on ever decreasing fish stocks too.) A lot of retail borrowing in Iceland was in Euros. The same applies to the Baltics and the Eastern rim of the Eurozone. Ambrose-Pierce admits this is a problem, noting that `Some 13% of households in Iceland hold mortgages in euros, Swiss francs, or God forbid, yen [and] some 70% of corporate loans are in foreign currencies.' That strikes me as a fact pattern that justifies Iceland's foreign currency debt rating. Clearly Iceland is on the up, but it is not out of the woods yet, and it won't be until investors are confident that it can pay its debt in their currency of denomination.

Labels: Sovereign Default

Wednesday, 29 July 2009

Moooo

Politicians Accused of Meddling in Bank RulesHe continues with more sound (if rather obvious) comment:

Accounting rules did not cause the financial crisis, and they still allow banks to overstate the value of their assets, an international group composed of current and former regulators and corporate officials said in a report to be released Tuesday.The report is here.

The report, from the Financial Crisis Advisory Group, also deplored successful efforts by politicians to force changes in accounting rules and said that accounting standards should be kept separate from regulatory standards, contrary to the desire of large banks.

Labels: Accounting

Tuesday, 28 July 2009

Corporate default rates by year and industry

Labels: Credit

Monday, 27 July 2009

Instability and the cover rule

The term 'covered' come from the early regulatory framework. In order to prove to the exchange that the issuer of the warrant could meet their obligations, they had to keep some or all of the underlying. This position in the underlying was known as the cover: it ensured that if the warrant ended up in the money, the issuer could deliver shares to the warrant holders. (Obviously if a corporate issues warrants on itself, then there is no problem: an entity can always print more of its own shares. The issue arises when a bank issues warrants referencing shares in another corporation, often without that corporation's permission or support.)

The cover requirements were supposed to ensure that squeezes did not happen whereby the issuer was forced to pay higher and higher prices to buy shares against the warrants that they hold. This is an issue with less liquid underlyings, especially ones where most of the liquidity is controlled by a small number of parties. By forcing banks to buy the underlying before issueing the warrant, exchanges made market disruption much less likely.

There is definitely something that we can learn from this piece of market history. When derivatives traders are forced by regulation to have a matching position in the underlying, then:

- There is a natural limit on the size of the market;

- Both derivatives and underlying markets are more orderly; and

- The issuer's risk is automatically limited.

The first is the CDS market. I am a supporter of this market, and I view many of those who wish to limit CDS trading as uninformed, hysterical or both. (People called Gillian who have a book to plug may well fall into this category.) However, there is one reasonable objection to CDS, and that is that it sometimes allows the tail (the derivatives market) to wag the dog (the underlying bond or loan market). I have no objection to letting people short credits, but doing so by CDS can provide more protection sellers than there are bonds, creating exactly the sort of squeeze post default that the cover requirements eliminated for warrants. The lack of a borrow market for corporate bonds is the real culprit here. Perhaps one solution would be to keep the CDS market as is, but to require that naked shorts pay a credit borrow fee to a holder of a deliverable instrument. This fee would be in exchange for the bond or loan holder agreeing not to buy protection on it or lend it to anyone else: the fee would automatically ensure that no more CDS protection was sold than there were bonds (or loans) extant which would at least make it more likely that the CDS settlement was orderly.

Second, the commodities market, specifically oil. This post was inspired by a fascinating article on the oil market from the Oil Drum (via FT alphaville). One part of the author's arguments is that the existence of an enormous market in financial contracts on oil has resulted in considerable price volatility - perhaps even price manipulation - which is in the interests neither of producers nor consumers of physical oil, but which benefits intermediaries such as the investment banks considerably. Certainly if one believed that this is true - and the evidence is impressive - then again the solution is obvious: require all derivatives positions to have a physical hedge. If you are short, then you have to own the underlying. If you are long, then you have to borrow the underlying. A given barrel of oil can act as the hedge for just one contract. And you can only use deliverable oil - stuff in tanks - not oil that is still in the ground.

Labels: Derivatives, Hedging, Markets

Sunday, 26 July 2009

This cancer

There are too many cars, they use too many resources, and there are too few credible alternatives to them. The Accord's trajectory is just a minor illustration of quite how screwed up we have allowed transport to become.

There are too many cars, they use too many resources, and there are too few credible alternatives to them. The Accord's trajectory is just a minor illustration of quite how screwed up we have allowed transport to become.Labels: Transport Policy

Saturday, 25 July 2009

Introducing Algo

Labels: Markets

Friday, 24 July 2009

Cry havoc and let slip the dogs of war accounting

The FASB says it may expand the use of fair-market values on corporate income statements and balance sheets in ways it never has before. Even loans would have to be carried on the balance sheet at fair value, under a preliminary decision reached July 15. The board might decide whether to issue a formal proposal on the matter as soon as next month.So the Americans are showing some guts. Good on them. This will be an interesting showdown. The FASB, in white hats, are holed up in a one horse town with the evil banker boys coming after them; their old allies, the IASB gang, have abandoned them, and they only have unarmed readers of financial statements supporting them.

Labels: Accounting

Thursday, 23 July 2009

Robust finance

Any engineer will tell you of the importance of making complex systems robust. You need inspections to prevent failure, to be sure: but since failures are inevitable it is equally important to try to ensure that the consequences of such failure are contained.Kay gets the solution wrong though. He suggests that the risky component as he sees it - investment banking - should be isolated from the rest. That's foolhardy on two grounds. First, it wasn't investment banking that caused the crisis. Derivatives weren't the problem, after all: it was mortgage lending. The lesson here is that the risk often isn't where you think it is, and so isolating the risky part of the business is not straightforward.

This observation is as relevant to economic and financial systems as to technological ones. Designing them with components too important to fail is a prelude to disaster, as we know. In the financial sector, the problem of disruptive linkages between components has become known as the problem of systemic risk... the main source of systemic risk is within large financial conglomerates themselves.

Instead we should accept that any component might fail, and thus to keep the linkages between all components sufficiently loose that no failure can bring the whole system down. That involves increasing capital and liquidity requirements, decreasing counterparty exposure, and taking a particularly conservative view of systemically important institutions.

Labels: Regulation

Wednesday, 22 July 2009

72%?

From Bloomberg:

From Bloomberg:Morgan Stanley set aside 72 percent of its second-quarter revenue for compensation and benefits, more than Goldman Sachs Group Inc. or JPMorgan Chase & Co.Why on earth do the shareholders tolerate this? That's nearly three quarters of their money, money that they as owners of the firm deserve, that is going out the doors again to employees. If I owned Morgan Stanley stock I would be outraged. Instead probably most of them have so little sense that they are probably buying wrapping paper for really large piles of money as you read this.

Labels: Compensation

39 Steps

The IAS 39 replacement project is proceeding in three phases:

- Classification and measurement

- Impairment methodology

- Hedge accounting

The current proposals are a bit of a curate's egg. The good parts first.

- The available for sale category is eliminated. All instruments are either held at fair value or amortised cost.

- The treatment of embedded derivatives is simplified.

- There will be only one approach to impairment, and it will be used for all instruments in the amortised cost category.

- Only loan-like instruments can valued using amortised cost.

The big problem, though, is the availability of amortised cost for some assets. Provided a financial asset is debt like, managed on a yield basis, and the institution's strategy is to hold it to maturity, then they will be able to use amortised cost accounting. This means that the ability to lie about what your assets are worth is preserved. It means that the same bond can be held at two different values by different institutions as one could use fair value and the other amortised cost. If a very firm approach is taken to impairment, and this approach is actually implemented by the audit firms, then perhaps this will not be a total disaster. But I still worry that the basic principle of true and fair has been obscured by the banks' desire to smooth earnings.

In their podcast -- even accountant standards setters make podcasts, -- the IASB say:

While fair value could provide useful additional information [for investors], the board believes that the cost of providing that information likely outweighs the benefits [in some cases].I have to say that I don't share this belief. I think that the benefits of trying to estimate fair value are great both for the reader of financial statement and for the preparer. Of course, finding fair value can be as hard as finding an allicorn, and there can be considerable subjectivity in the process. But I still want to know what an institution estimates its assets are worth now, not what they might be worth if their strategy is successful.

Labels: Accounting

Tuesday, 21 July 2009

The modifier on innovation

So, what do we know? First that certain infrastructures help innovations generate wealth. The ability to profit from a good idea helps, as does the ability to finance development. Hence patents and joint stock companies. Education is necessary, and law which gives certainty of ownership is also helpful.

Next, we know that most innovation does not produce growth. A lot of it isn't harmful, but there are many, many dead ends. Markets are sometimes (but not always) good at sorting out which ideas are useful.

Now to specifically financial innovation. The point of financial innovation is to produce products which meet specific needs better (more cheaply, more accurately), and thus often to lower the cost of finance. Some innovations have worked out: a good example would be the convertible bond, which allows companies to monetise the volatility in their stock price. Others have been more or less useless but benign. Credit spread options are a good example here: in the early days of credit derivatives, these were a competitor with CDS as standard credit risk transfer products. CDS turned out to work rather better, and so credit spread options faded into illiquidity without doing anyone any harm.

Are there genuinely harmful wholesale financial products? I am still not sure that there are. I certainly can't think of one*. If firms are required to keep enough capital against the risk of a product; to value it properly; and to document it carefully, then why should trading be constrained? Isn't product licensing just a route to a less efficient economy?

*Tradable emissions permits come pretty close though.

Update. There is a nice rebuttal of the `innovation causes crises' meme from the Economics of Contempt here.

Labels: Economic Theory, Intellectual Capital

Monday, 20 July 2009

A small town in Switzerland, part 3

Factors that are deemed relevant for pricing should be included as risk factors in the value-at-risk model.If you took the committee at its word, here, no one would have a VAR model. Just consider an equity derivatives book on underlyings in the Eurostoxx. There are 50 underlyings, 50 dividend yields (more if you consider the term structure of dividend yields), at least 20 interest rates in Euros, and as many implied volatilities as you have (strike, maturity) pairs for your options. A decent sized book will have many hundreds, perhaps many thousands, of risk factors. No one has a VAR model with all of those factors in it. So, what is a bank to do? Let's turn back to the committee:

Where a risk factor is incorporated in a pricing model but not in the value-at-risk model, the bank must justify this omission to the satisfaction of its supervisor.Ah lovely. So if you have a tolerant supervisor, perhaps because you are in a small country, or because you are a national champion bank, all is well. If not, you will have some hoops to jump. This provision in short is a charter for regulatory arbitrage. The next part is even worse:

In addition, the value-at-risk model must capture nonlinearities for options and other relevant products (e.g. mortgage-backed securities, tranched exposures or n-th-to-default credit derivatives), as well as correlation risk and basis risk (e.g. between credit default swaps and bonds). Moreover, the supervisor has to be satisfied that proxies are used which show a good track record for the actual position held (i.e. an equity index for a position in an individual stock).If this doesn't make players with big trading books redomicile to somewhere small, low tax and friendly, I don't know what will.

Labels: Basel, Regulation

Sunday, 19 July 2009

When a technology dies...

Saturday, 18 July 2009

Well that went well I think

In their latest research report, Wells Fargo (formerly Wachovia) analysts calculate that 360 CDO of ABS have now triggered an event of default – up from 343 last month. At $351.6 billion, the notional value of these deals accounts for just over half of all CDOs of ABS.

Labels: ABS

Friday, 17 July 2009

A small town in Switzerland, part 2

Two things spring to mind at once. The classifying criteria is rating. That's right - the ratings agencies, who did such a sterling job at rating ABS that they are facing multiple lawsuits and much approbrium, are still at the heart of regulatory capital. And given that, 20% is hardly penal for a AAA CDO squared tranche. Roll on re REMIC.

Two things spring to mind at once. The classifying criteria is rating. That's right - the ratings agencies, who did such a sterling job at rating ABS that they are facing multiple lawsuits and much approbrium, are still at the heart of regulatory capital. And given that, 20% is hardly penal for a AAA CDO squared tranche. Roll on re REMIC.Labels: Basel

Is Goldman just a credit punt?

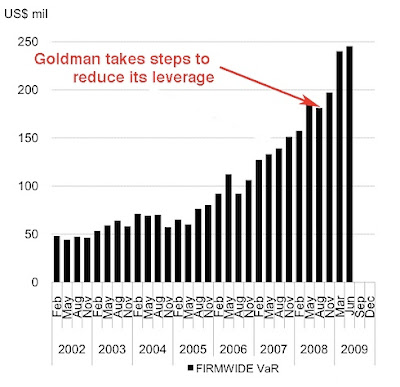

The Big Picture suggests that it might be, and provides this initially compelling illustration (which I have edited slightly to make it less confusing). However, I think that what we are really seeing is that both overall credit spreads and Goldman's stock price are driven by confidence. The more economic activity there is, the more money Goldman can make from the flow. A similar phenomenon was observable with the Merrill stock price in the 90s -- it acted like a call on the S&P, for similar reasons.

Update. Given ...the furore about Goldman's continued use of a SEC rather than FED VAR calculation, despite being a bank holding company, I am driven to wonder how big Goldie's IRC is. If it is just a giant credit punt, one might expect it to be enormous...

Labels: Markets

Thursday, 16 July 2009

A small town in Switzerland, part 1

[My interpretation of the scope of the IRC is based on the following text from BCBS159: 'the IRC encompasses all positions subject to a capital charge for specific interest rate risk according to the internal models approach to specific market risk but not subject to the treatment outlined in paragraphs 712(iii) to 712(vii) of the Basel II Framework', 712(iii) to (vii) being the standard rules approaches for specific risk. Caveat lector.]

Labels: Basel

Wednesday, 15 July 2009

The world's least favourite airline

BA has become an institution run not for the benefit of its customers – who provide its revenue – but for its staff and pensioners. Its shareholders, meanwhile, have long been forgotten.If a firm like BA isn't a conviction short, I don't know what is.

Labels: Markets, Organisational Culture

Tuesday, 14 July 2009

Monday, 13 July 2009

Taking out the leverage

The private equity industry has known this for a long time. By structuring an investment as unlisted equity, they have been able to take advantage of good opportunities with uncertain payback horizons. The example the FT cites is a real estate investment, an area which has not historically been favoured by private equity, but these are new times. (Another area where equity like financing is preferred is of course sharia-compliant finance, but that is another story.)

Reequitisation, then, is a logical trend. After the recent turmoil, many investors would be happy with boring, safe investments that beat cash. If zero or low leverage equity investments in cash cow assets provide that, then for a while at least, investors will be buying them with alacrity.

Update. There is an article with a similar theme, albeit dressed up in rather grandiose language, in the FT.

Labels: Securitisation, Tranching

Sunday, 12 July 2009

Do loan mods reduce delinquency rates?

If you get into trouble on a mortgage, and you are American, and you are offered a loan modification, it is unlikely to help much. The following data is from the Big Picture. Barry explains:

On the left we see the re-default rates of homeowners who were current on their loans when they first defaulted (sounds odd, I know, but these tend to be people who can afford their homes but who subsequently ran into economic problems). The data tells us how many of them have defaulted again 10 months after their loans were modified.

The adjacent table (at right) shows the same thing, only this time with homeowers who were seriously delinquent prior to loan mods. As you would imagine, their re-default rates 10 months after their loans were modified are considerably higher. These are often the people who could barely afford their home (or not at all).

Saturday, 11 July 2009

Friday, 10 July 2009

Understanding ABS

It's important for people to realize that the credit crunch was not caused by securitization -- it was caused by very poor assumptions used to rate securitizations. In a different world, with smarter rating agencies and investors who did due diligence, things might have turned out better. The future of finance should not exclude securitization. It should continue to be utilized, just with better assumptions.It is worth noting, though, that securitisation did faciliate the crunch since it allowed the interests of those making loans to diverge dramatically from the interests of those holding the risk of those loans.

Another key issue is that people didn't - and to some extent still don't - understand the risks of ABS. An ABS is not like a corporate bond for a number of reasons. First, many of these securities have uncertain duration: if things go well, they can have quite a short weighted average life; whereas if things go less well, you can be on risk for much longer. Second, in a corporate bond, management have real options: they can sell parts of the business, pledge assets to raise liquidity and so on; in an ABS, in contrast, (at least if the collateral pool is not managed), you are stuck with the assets for better or for worse. Third, the credit enhancement in ABS often means that the expected probability of default is low but the loss given default is very high. Corporate bonds may well have a higher recovery. Hence there can be a huge difference between the expected losses on two securities with the same probability of default. None of this means that ABS are necessarily toxic, but it does mean that the buyers of these securities need to understand these risks in detail. More conservative ratings will help, but a single rating alone can never be enough to distinguish the complex risks of ABS.

Labels: ABS, Securitisation, Tranching

Thursday, 9 July 2009

AAA to A3 check, 2/3 A3 to AAA mate

My only question, really, is if these new bonds are downgraded too, will someone else step in and ReRe-Remic them?

Wednesday, 8 July 2009

Growth vs. Stability

There is a tradeoff between growth and financial instability. The system can be worse than the limit - more unstable or slower growing - but it cannot be better.One of the reasons I think that something like this might be true is that a supply of cheap credit allows faster growth, but at the cost of instability when there is a downturn. A recent article in the FT supports this. As you might expect, securitisation - the primary cheap credit channel - has come to a grindng halt in many areas.

As the FT says:

As the FT says:...the freeze in securitisation markets has led to a dramatic shortage of lending power – a “credit crunch”. Thus the policy question now is whether there is any way to restart or replace this securitisation “motor” to stop the economy slowing further.This implies of course that faster growth is necessarily a good thing. If the conjecture is correct, then shouldn't we have a discussion about its consequences rather than going broke for growth again?

Labels: Securitisation

Tuesday, 7 July 2009

FSA gets medium rare

The City regulator said some fines could treble in size as it seeks to address concerns that penalties thus far have not proved much of a deterrent in improving company behaviour.Why not 100%? Why not 'all their assets'? Drug dealers have all of their assets seized - are we really saying that selling grass to make thousands is completely evil, but insider trading for millions is only 40% evil?

It also announced proposals for a minimum fine of £100,000 for individuals found guilty of market abuse offences such as insider dealing. Up to 40 per cent of an individual's salary and benefits could be taken, it said.

Labels: Regulation

Monday, 6 July 2009

Titled Coffee

Labels: Fun

Counter-cyclical capital

Labels: Basel, Capital, Regulation

Sunday, 5 July 2009

Meritocractic mistakes

The principle says, of course, that people climb in an organization until they reach their level of maximum incompetence...

Kedrosky discusses a simulation of organisational behaviour with meritocratic promotions and where competence in a new job has low correlation with competence at a prior level.

The authors simulated the preceding in a pyramidal organizational form using a mathematical agent model. Here is the outcome...And, of course, random promotions are better for the organisation than meritocratic ones. The source material is here. Now just try telling that to the HR bots...

not only the "Peter principle" is unavoidable, but it yields in turn a significant reduction of the global efficiency of the organization.

Labels: Organisation Structure

Just privatise them?

Update. Felix Salmon has a fascinating piece on the costs of driving in cities here, and how sensible congestion charging combined with fare revisions can make everyone's travel more efficient. While I am not convinced that fixed pricing is the right approach - letting investment bankers who can afford it drive while less highly waged workers are forced onto the subway - there are clearly some very interesting results in the work Felix describes. The right approach would be a variable tarif based on income, so that the congestion charge depends on how much grief you cause other people, how much carbon you emit, and how much you earn, but that is politically impossible.

Labels: Transport Policy

Saturday, 4 July 2009

Skin in the game

The evidence from a huge national database containing millions of individual loans strongly suggests that the single most important factor is whether the homeowner has negative equity in a house -- that is, the balance of the mortgage is greater than the value of the house. This means that most government policies being discussed to remedy woes in the housing market are misdirected...This isn't exactly news, but it is further confirmation of a fact that has been clear since 2007 - alignment of interests is key in the credit markets.

51% of all foreclosed homes had prime loans, not subprime, and the foreclosure rate for prime loans grew by 488% compared to a growth rate of 200% for subprime foreclosures.

Labels: Mortgage

Friday, 3 July 2009

Shotguns and blowups

From Mark Gilbert on Bloomberg:

From Mark Gilbert on Bloomberg:If the aftermath of the credit crunch is a financial landscape featuring fewer banks, each even bigger than before because of government-engineered mergers and opportunistic takeovers of weaker brethren, then we should all be very afraid. That, though, is exactly where we are headed.The whole article is spot on: I recommend it.

Labels: MOAB, Regulation

Thursday, 2 July 2009

Reality and perception in equity markets

Labels: Markets

Wednesday, 1 July 2009

The Axiom of Choice and Other Fallacies

Well... not quite. The problem comes when the set becomes infinite. Then how you tell me what you have picked becomes an issue. If the set is only countably big, so that you can number the elements 1, 2, 3 and so on, it isn't an issue - you say `I pick element 14,784,...' or whatever. But if the set is bigger than that, for instance it has the same cardinality as the real line, then specifying what you have picked gets harder.

In particular, set theorists have proved adept at constructing very large sets indeed - the boundary of `stupidly big' starts somewhere around the totally ineffable cardinals. For these babies, specifying the choice that you have made requires so much information that some mathematicians reject the axiom of choice as not effective. Basically they think that if you can't say what you have chosen without ridiculous amounts of information, then you can't choose. It also turned out that full AOC was equivalent to other principles that people found troubling, such as the law of the excluded middle. Some mathematicians therefore rejected full AOC, accepting only the axiom of choice when applied to `reasonable small' sets. (Thus we get for instance realizable versions of AOC, where you can apply AOC to `nice' sets.)

So what, economics lovers? Well, it turns out if Chris Ayers is to be believed that lots of economics relies on AOC

All current solution concepts in game theory also require the theorems implied by AC. In particular, lexicographic utility, lexicographic probability, the real line being well-ordered, and the existence of a universal space are all equivalent to AC; therefore any argument to disprove their existence must be false. Any proofs using properties that fail under AC must be redone. The concept of Nash Equilibrium becomes either a tautology (in the absence of AC) or violates rationality (in the presence of AC); we provide an example demonstrating this.My strong suspicion is that this is a storm in a teacup and that even if Ayers' result is true (which it may well not be - caveat lector), you can get by with a weaker `effective' version of AC by considering suitable realizable outcomes. You'd end up with a smaller collection of games, but this would probably include realizable versions of all of the interesting ones. Still, even if this is nonsense, the idea of setting up game theory in a more effective setting is interesting.

Update. A cursory search doesn't reveal any academic association for Mr. Ayers. And the proof of the first theorem is wrong. That's not a proof that Ayers is a charlatan, of course, but should make one more sensitive to the possibility.

Labels: Foundations

Fixing monopolies

Labels: Markets

Tuesday, 30 June 2009

20%

This very clearly shows how investors let their standards slip in the hurt for yield during the Boom years. Not everyone was convinced though: from 2004 the practice of splitting the AAA into two or more tranches became commonplace. The top tranche, amusingly, is called super duper AAA.

This very clearly shows how investors let their standards slip in the hurt for yield during the Boom years. Not everyone was convinced though: from 2004 the practice of splitting the AAA into two or more tranches became commonplace. The top tranche, amusingly, is called super duper AAA.S&P want at least 19% credit enhancement for AAA going forward. At least this is generating a nice repack business as banks take junior AAAs and resecuritise to keep most of the notional at AAA. The Americans call this a Re-Remic* -- which isn't nearly as cool sounding as super duper AAA.

* Real estate mortgage investment conduit, or CDO-squared to its friends.

Monday, 29 June 2009

Physics envy, History envy

As a result, some practioners in other fields have physics envy. This is a notable problem for finance quants, many of whom didn't make it as academic physicists (or did make but didn't like the salaries). Indeed in retrospect one can make a case that one of the causes of the Credit Crunch was the collapse of the Soviet Union - the argument would go that the collapse freed up lots of highly trained mathematians and physicists, some of whom came to work for investment banks - no bulge bracket firm was without its Academy of Sciences prize winner; the geeks used used the maths that they knew, which was mostly stochastic calculus, to model things; these models were dangerous but not easy to falsify (because they were only really wrong in a crisis); so the industry used them and was subsequently screwed. In one way at least communism brought capitalism down with it.

Anyway, the desire to build highly mathematical models has in practice lead finance down a dangerous path. Perhaps the aspiration was good, but the implementation has been deeply flawed.

Let me instead propose a different aspiration. History envy. History is a lovely subject. There are lots of facts, but most historians ignore many of the relevant ones. They are interested in motivations, in causes, in the evolution of ideas. They want to understand the why as well as the what. A good history text is carefully argued and insightful. It provokes discussion, and casts fresh light on the present. It's not clearly wrong, given the evidence, but it can never be said to be right, either.

How much better would finance be if it took these desiderata? Abandon the spurious and misleading quest for quantification. Just try to make an interesting argument about why things happen.

Labels: Financial Models

Sunday, 28 June 2009

Most expensive cities for residential property

Hong Kong is a special case, being an island where much of the undeveloped land is owned by the government, but the others do certainly look like short candidates. Chinese property derivatives anyone?

Hong Kong is a special case, being an island where much of the undeveloped land is owned by the government, but the others do certainly look like short candidates. Chinese property derivatives anyone?Labels: Markets

Restructuring and bankruptcy

the first major restructuring that I can remember being significantly hindered by CDS was Marconi, and that was back in 2001-2002. Marconi was negotiating a restructuring with a bank syndicate, but for a long time certain syndicate participants (cough, UBS, cough cough) refused to agree to any restructuring that didn't constitute a "credit event" under the 1999 ISDA Credit Derivatives Definitions. The holdout banks had purchased CDS on Marconi to hedge their exposure, and if they were going to agree to a pretty drastic restructuring, they wanted to make sure they got the benefit of their hedges. After more than a year of restructuring negotiations, the banks agreed to a debt-for-equity swap that qualified as a credit event under most of the CDS contracts, but also pretty much wiped out shareholders.I'm not personally familiar with Mirant, but the Marconi example is certainly a good one. There is a definitely a good case that rights to sit at the creditors table should sit with the risk holder, not the bond holder.

Mirant Corp.'s 2003 bankruptcy was also largely a result of CDS. Several creditors had purchased CDS protection on Mirant, and one major creditor in particular, which rhymes with Pitigroup, was relatively open about the fact that it didn't agree to a restructuring because it needed a bankruptcy filing to trigger its CDS contracts referencing Mirant. The bank that rhymes with Pitigroup's refusal to agree to a restructuring (which came at the last minute and was a big surprise, if I remember correctly) effectively torpedoed any chance Mirant had of avoiding bankruptcy.

Labels: CDS

Saturday, 27 June 2009

Seriously antiquated

FED, OCC, OTS, FHFA, CFTC, SEC, FDIC, NAIC, ...

It seems that Obama and co. do not have the balls to sort out the alphabetic mess that is US supervision. Even the obvious targets - the OTS, who supervised AIG (yes, technically AIG was a Thrift), the SEC's regulatory capital regime, which did such a good job there are zero out of five large firms left on it - may be left to waddle on. Antiques may have an attractive patina, but sometimes you need something that is fit for the modern age. We won't get it, though. I am very tempted, like .the Epicuran Dealmaker, to give up on this crap

Labels: Regulation

Friday, 26 June 2009

The types of instability

Belated the SEC has proposed revisions to the regulatory framework for funds: see here for a prospectus.

What these proposals will do is turn a nasty dynamic destabiliser into a static one. Since funds will be unable to invest in low quality instruments, they will not be able to fund lower quality firms at all. In effect the barrier to entry for the big boys club will get higher.

Labels: Money Market

Thursday, 25 June 2009

Honour

'My word is my bond' are old words: 'My word is my CDO-squared' will never catch on.He's right, but it is a shame. After all, we need a convenient shorthand for 'My word is badly structured and likely to lead you into trouble'.

Labels: CDS

Wednesday, 24 June 2009

The loneliness of the long distance regulator

there should instead be a "tax on size" by requiring the big banks to set aside more capital when they expanded beyond a certain size.Quite right too, and nice to see an idea I championed being mentioned in such august circles. The bad news is that

Turner also warned the MPs that the radical changes to regulations needed in the wake of the banking crisis may not take place because of the emergence of green shoots of recovery and "exhaustion".Regulatory reform is a marathon not a sprint and I share Turner's doubts that we have the stamina to do a good job at it.

Labels: Capital, Regulation

Tuesday, 23 June 2009

Post of the day

Labels: CDS

Before the bust: AIG's early collateral postings

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Societe Generale SA extracted about $11.4 billion from American International Group Inc. before the insurer’s collapse as the firms demanded to hold cash against losses on mortgage-linked securities, ... “It was precisely that drain of liquidity to Goldman and SocGen that put AIG in a position of illiquidity and ultimately threw them into the government’s arms,” said Charles Calomiris, a finance professor.

Including collateral from before and after the rescue and payments made by Maiden Lane III, a vehicle created by the Fed to retire the swaps, Goldman Sachs received about $14 billion from AIG, Societe Generale got $16.5 billion, and Deutsche Bank AG received $8.5 billion.

Monday, 22 June 2009

Cash up front please

The banking industry could be told in advance that, if ever there was another crisis, the ultimate cost would come from banks themselves. In the midst of a crisis, that would not be possible. A government would have to pump in new equity. But when the dust had settled and the government had sold its shares, the loss (if any) could be calculated - and then collected from the industry via a levy.This isn't a bad idea. But there is a better one. Make them pay before the crisis.

There are various ways to do this. One is to take cash from the banks, via a beefed up version of the way the FDIC works. In order to be a financial institution, you need an annually renewable license, and the license should be expensive.

A more intriguing one, though, is to make the banks hand over each year not cash, but one year call options on their stock. The regulator would then hedge these options. The bank's shareholders would only be diluted if the stock went up, sugaring the pill for them, while the hedging process would ensure the regulator made money whether the stock went up or down. Indeed, as the position is long gamma, a big fall would be particularly profitable to the hedging strategy.

Labels: Capital, Gamma, Hedging, Regulation

Each way bet

Here's a nice little section. The speaker is talking about Pascal's wager. He generalises:

Today the possibility of making the wager has shifted from metaphysics to history... I would risk losing everything were I to bet against the revolution. But if I bet on it, I lose nothing if it doesn't take place. I win everything if it does.I feel the same way about regulatory reform. If it isn't necessary and we do it properly, we lose very little. But if it is -- if failure to reform just bakes more systemic risk into the financial system - then failing to reform properly means that we lose a great deal. In this context the gutless Obama plan is worse than thin: it is a bet that may ruin us.

Labels: Regulation

Sunday, 21 June 2009

Chop the tail off a 911 or something...

Please accept my apologies for the scarcity of postings - I have been in Berlin. There will be more soon but meanwhile, here's a tip from the locals. Short Porsche. Porsche's short options position on VW expired on Friday, and it is thought that they escaped by the skin of their teeth, but the firm's debt burden is a serious problem.

Please accept my apologies for the scarcity of postings - I have been in Berlin. There will be more soon but meanwhile, here's a tip from the locals. Short Porsche. Porsche's short options position on VW expired on Friday, and it is thought that they escaped by the skin of their teeth, but the firm's debt burden is a serious problem.Labels: Markets

Saturday, 20 June 2009

Wednesday, 17 June 2009

5% is not much

Labels: Regulation, Securitisation

Tuesday, 16 June 2009

The Amherst Trade

The newswires have been buzzing recently with news of a 'daring' CDS trade by Amherst Holdings. I didn't comment on it at first as I didn't understand the trade from the initial news items, but I now think it is possible to work out what's going on.

Let's start with the bonds this trade refers to. They are subprime MBS. Like most MBS, these are amortising, prepayable bonds. The fact that these are amortising bonds means that the face value of the security is irrelevant: what counts is the principal balance at the time the trade was done. [Quite a lot of the stories were confused about this point, so it is worth pointing out.]

So, let's say we have some bonds with $100M left to repay.

The next bit that is tricky is the nature of the CDS protection sold. Everyone agrees Amherst sold protection and some banks bought it. But what protection exactly? It is most common for CDS on MBS to be pay as you go, meaning that the protection sellers compensates the protection buyer for principal deficiencies as and when they occur. There is no event of default as such, unlike corporate CDS. [To be strictly honest, there may be an event of default as well, such as bankruptcy of the issuing SPV, but that is irrelevant for our purposes.]

Let's suppose then that Amherst sold pay as you go protection on $100M of bonds.

Since the bonds were thought likely to repay little to nothing of the outstanding principal balance, the banks paid Amherst, say, $80M up front for their protection. [There may have been an ongoing coupon as well, but we'll ignore that.]

Amherst then paid the servicer to buy out the underlying mortgages and pay off the bonds. Thus the bond holders got their $100M. The servicer could do this because the bonds had a 10% clean up call, meaning that if more than 90% of the face had amortised, they could repay the remaining principal balance at any time. [So to keep with the example, the face amount was more than $1B.] 10% cleanup calls are common in ABS, and they are what makes Amherst's trade work*.

Now, here's the confusing part. Who won and who lost?

First the banks. If they had held the bonds, then they would be about flat. $80M for CDS protection paid out, but $100M paid back is a $20M profit, from which subtract the (few cents) cost of the bonds. So the only way the banks could have lost massively on the trade, as reported, would have been if they had been net short the bonds. That is, they did not own the bonds, and bought protection, betting that total losses would be more than $80M. The losers, then, were parties who did not own the bonds and who did not realise the significance of the cleanup call to their short.

[The WSJ story suggests that JP Morgan lost money but that RBS and BofA didn't. This would be consistent with JP being net short, while RBS and BofA had a negative basis trade on, i.e. owned the bonds and bought CDS on them. The presence of net shorts is also consistent with the WSJ's suggestion that more protection had been traded than the notional of bonds outstanding.]

Next Amherst. They had the $80M of CDS premium. But how much did they have to pay to get the bonds repaid? Clearly a logical answer would be about $80M. Therefore the only way that Amherst could have made money would have been if they had sold more protection than there were bonds - $200M say rather than $100M. Say they sold $50M to JPM, $50M to RBS and $50M to BofA. Then they would have had to pay $80M, roughly, to buy back the mortgages behind the RBS and BofA CDS, but the JPM CDS was not backed by any bonds and so the $40M premium from JPM would be straight profit.

In other words, the only way Amherst could have made a lot of money on this trade would have been if it sold more protection than there were bonds. The only way that the banks could have lost money would have been if they bought more protection than there were bonds. In a situation like this someone was always going to be squeezed. It's just that this time, that party wasn't an investment bank.

The lesson of this amusing little situation? Nothing more than read the small print. The buyers of protection -- and in particular naked shorts -- should have understood that arbitrary action by servicers is possible, and that in particular the 10% clean up call could be exercised. This is a much bigger risk late in the amortisation profile of a bond than early, but it is there for most ABS. Caveat emptor.

* Contrary to what Willem Buiter writes in his blog, if you own 100% of a bond, you cannot necessarily control whether it defaults or not. A default on a public security is a default, regardless of who is affected.

Another mistake Buiter makes is assuming that centralising CDS trading would not have helped in this situation. It would certainly have helped the banks to avoid their losses, in that the size of Amherst's long vs. the cash would have been obvious thanks to trade reporting. Personally I don't particularly feel the need to help the CDS trading desks of investment banks, mind you.

Labels: ABS, CDS, Legal Risk, Trade Documentation